Insider Brief

- MIT CSAIL, with Toyota Research Institute and Amazon support, unveiled “steerable scene generation” to mass-produce realistic 3D environments that close the sim-to-real data gap for training robots.

- The system trains on 44M 3D rooms and steers a diffusion model with Monte Carlo Tree Search and reinforcement learning to create physically consistent scenes, scaling complexity (e.g., up to 34 objects vs. 17 on average).

- It reliably follows text prompts (≈98% for pantry shelves; ≈86% for messy tables) and yields repeatable task demonstrations, enabling safer, faster training for household and industrial manipulation.

Backed by funding from Amazon and the Toyota Research Institute, researchers at MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL) have built a system that can mass-produce realistic 3D scenes for training robots—an attempt to solve one of robotics’ most stubborn bottlenecks: getting enough high-quality, physically accurate “how-to” data.

The team’s “steerable scene generation” method aims to shrink the gap between tidy simulations and the messy real world, a prerequisite for robots that can reliably load dishwashers, sort packages, or restock shelves, according to MIT.

The work starts from a basic truth: text-only data made chatbots useful, but it won’t teach a robot how to pick up a fork or stack plates without knocking them over. Robots learn those skills from demonstrations—step-by-step examples that show where objects are, how they move, and what physical constraints matter. Collecting that data on real machines is slow and hard to repeat, while hand-building synthetic worlds rarely captures real-world physics. MIT and and Toyota Research Institue researchers’ answer is a generator that can spin up lifelike kitchens, living rooms, restaurants, and pantries on demand, then place and orient thousands of objects in ways that obey common sense and contact physics.

The system is trained on more than 44 million 3D rooms populated with everyday items—tables, bowls, utensils, boxes—and then “steered” to produce scenes that meet a chosen objective. Under the hood is a diffusion model, a popular image-generation technique that starts with visual noise and gradually sharpens it into a coherent picture. Here, the generator “in-paints” a space by filling in missing elements and repeatedly refining their positions so objects don’t intersect or float—avoiding the graphics glitch known as clipping.

What makes the approach flexible is how that steering works, MIT noted. The primary strategy is Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS), the decision-planning method used in game-playing AI systems. The researchers frame scene building as a series of choices: add this object or that one; move a plate here or a cup there; keep or discard an arrangement based on the objective. The search explores many partial scenes and keeps improving them, which lets the generator create layouts more complex than those it saw in training. In tests, the method doubled the typical object count the model started with, populating a simple restaurant table with as many as 34 items after training on scenes that averaged 17.

“We are the first to apply MCTS to scene generation by framing the scene generation task as a sequential decision-making process,” noted MIT Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science (EECS) PhD student Nicholas Pfaff, who is a CSAIL researcher and a lead author on the paper presenting the work. “We keep building on top of partial scenes to produce better or more desired scenes over time. As a result, MCTS creates scenes that are more complex than what the diffusion model was trained on.”

A second steering mode uses reinforcement learning. After the initial training, the team assigns a reward tied to a goal—for example, a penalty when objects intersect or a bonus for placing more edible items within reach. Through trial and error, the generator learns to produce higher-scoring scenes that differ from the original dataset but remain physically plausible.

The system can also follow plain-language prompts, turning requests such as “a kitchen with four apples and a bowl on the table” into 3D layouts with high fidelity. In controlled evaluations, the generator satisfied prompts for pantry shelves 98% of the time and for cluttered breakfast tables 86% of the time—at least ten percentage points better than comparable methods cited by the MIT team (including MiDiffusion and DiffuScene). Users can ask for variations—rearranging the same objects into a new layout, or filling empty spaces with additional items—while the engine preserves the rest of the scene.

Crucially for roboticists, the output is useful. The researchers recorded virtual robots performing tasks across the generated environments—sliding forks and knives into a cutlery holder, placing bread on plates—yielding repeatable training data without risking damaged hardware. Because scenes are physically consistent, small adjustments in object pose or contact lead to realistic differences in the resulting motion, the kind of nuance robots need to transfer skills from simulation to real settings, researchdders pointed out.

The team stresses that this is a foundation, not a finish line. Next steps include generating entirely new object models (rather than relying only on a fixed asset library), adding articulated items such as cabinets and jars that open and twist, and pulling in web-scale image collections to make virtual environments even closer to the real world. The researchers also point to earlier work on “Scalable Real2Sim,” which converts real images into simulation assets; combining such pipelines with steerable generation could seed a community that continuously contributes scenes and interactions for others to reuse.

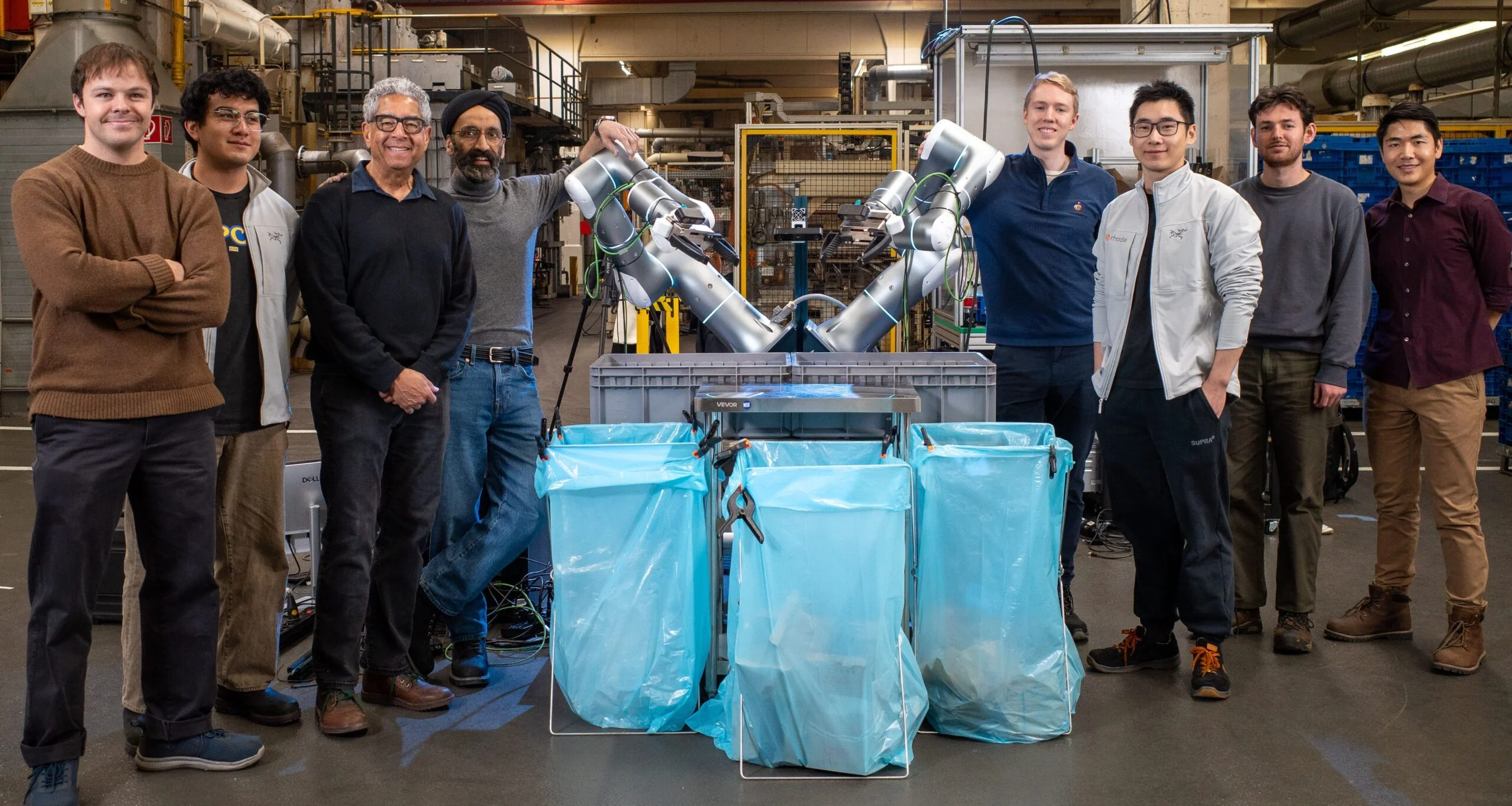

The study—led by MIT CSAIL PhD student Nicholas Pfaff with senior author Russ Tedrake (MIT; Toyota Research Institute) and co-authors Hongkai Dai and Sergey Zakharov of Toyota Research Institute and Shun Iwase of Carnegie Mellon University—was presented at the Conference on Robot Learning (CoRL) in September. MIT credits support, in part, from Amazon and the Toyota Research Institute.

Image credit: MIT