Insider Brief

- MIT researchers have developed VaxSeer, an AI system that predicts which influenza strains will dominate and which vaccines will offer the best protection, aiming to reduce guesswork in seasonal flu vaccine selection.

- Using deep learning on decades of viral sequences and lab data, VaxSeer outperformed the World Health Organization’s strain choices in 9 of 10 seasons for H3N2 and 6 of 10 for H1N1 in retrospective tests.

- Published in Nature Medicine, the study suggests VaxSeer could improve vaccine effectiveness and may eventually be applied to other rapidly evolving health threats such as antibiotic resistance or drug-resistant cancers.

MIT researchers have unveiled an artificial intelligence tool designed to improve how seasonal influenza vaccines are chosen, potentially reducing the guesswork that often leaves health officials a step behind the fast-mutating virus.

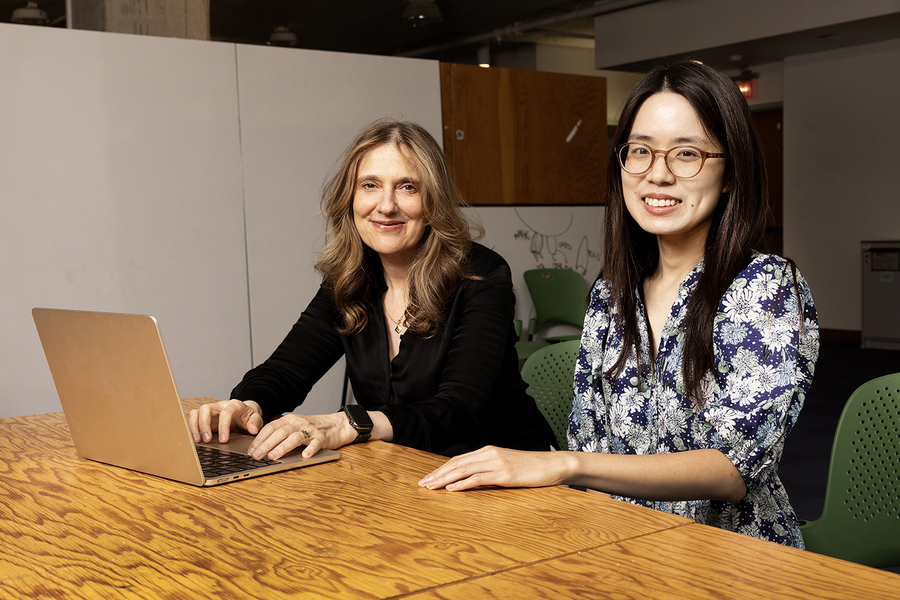

The study, published in Nature Medicine, was authored by lead researcher Wenxian Shi along with Regina Barzilay, Jeremy Wohlwend, and Menghua Wu. It was supported in part by the U.S. Defense Threat Reduction Agency and MIT’s Jameel Clinic.

According to MIT, the system, called VaxSeer, was developed by scientists at MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory and the MIT Jameel Clinic for Machine Learning in Health. It uses deep learning models trained on decades of viral sequences and lab results to forecast which flu strains are most likely to dominate and how well candidate vaccines will work against them. Unlike traditional approaches that evaluate single mutations in isolation, VaxSeer’s large protein language model can capture the combined effects of multiple mutations and model shifting viral dominance more accurately.

“VaxSeer adopts a large protein language model to learn the relationship between dominance and the combinatorial effects of mutations,” Shi noted. “Unlike existing protein language models that assume a static distribution of viral variants, we model dynamic dominance shifts, making it better suited for rapidly evolving viruses like influenza.”

In retrospective tests covering ten years of flu seasons, VaxSeer’s strain recommendations outperformed those of the World Health Organization in nine of ten cases for H3N2 influenza, and in six of ten cases for H1N1, researchers said. In one notable example, the system correctly identified a strain for 2016 that the WHO did not adopt until the following year. Its predictions also showed strong correlation with vaccine effectiveness estimates reported by U.S., Canadian, and European surveillance networks.

The tool works in two parts: one model predicts which viral strains are most likely to spread, while another evaluates how effectively antibodies from vaccines can neutralize them in common hemagglutination inhibition assays. These predictions are then combined into a coverage score, which estimates the likely effectiveness of a candidate vaccine months before flu season begins.

“Given the speed of viral evolution, current therapeutic development often lags behind. VaxSeer is our attempt to catch up,” Barzilay noted.