Insider Brief

- ETH Zurich researchers have developed MetaGraph, a framework that allows Google-like searches across 67 petabases of global genetic data at a fraction of previous storage and computational costs.

- The system uses annotated de Bruijn graphs and modular compression to index DNA, RNA and protein sequences, producing data structures up to 150 times smaller than existing methods while maintaining high search speed.

- MetaGraph enabled real-time discovery of links between viruses and antibiotic-resistance genes and identification of thousands of new circular RNAs, signaling a major step toward searchable, AI-ready genomic databases.

A team of scientists at ETH Zurich has created a framework that makes it possible to search the world’s vast troves of genetic data almost as easily as performing a web search. In a study published in Nature, the researchers describe MetaGraph, a system that indexes 67 petabases of publicly available DNA, RNA and protein sequences — equivalent to tens of millions of biological samples — at a fraction of the storage and computational cost previously thought possible.

Over the past decade, high-throughput sequencing has generated an avalanche of biological data. Repositories like the European Nucleotide Archive and the U.S. National Center for Biotechnology Information’s Sequence Read Archive now contain more than 100 petabases of raw genetic material from every branch of life. But accessing these datasets has required researchers to download vast files and process them with specialized tools, limiting their usefulness for large-scale discovery.

MetaGraph changes that by using compressed data structures called annotated de Bruijn graphs. The system enables full-text search across raw sequencing data. Each sequence is broken into short fragments known as k-mers, which are stored in a highly efficient graph-based index. This allows scientists to ask whether a particular genetic pattern — say, a gene variant or viral sequence — appears anywhere in the global data pool, without downloading or reanalyzing entire datasets.

According to the study, MetaGraph can perform these searches across 67 petabases of raw data at an on-demand cost of roughly $100 for small queries and as low as $0.74 per megabase for large searches. A complete index of all public sequences would occupy just 223 terabytes—small enough to fit on a few consumer hard drives costing about $2,500.

Technical Foundations and Performance

To achieve such efficiency, MetaGraph relies on modular, lossless compression techniques developed by the ETH Zurich team. The framework uses a two-part structure: a k-mer dictionary that records every short sequence, and an annotation matrix that links those sequences to metadata such as the originating sample or species. Together, they enable rapid lookup, alignment, and assembly tasks across datasets of unprecedented size.

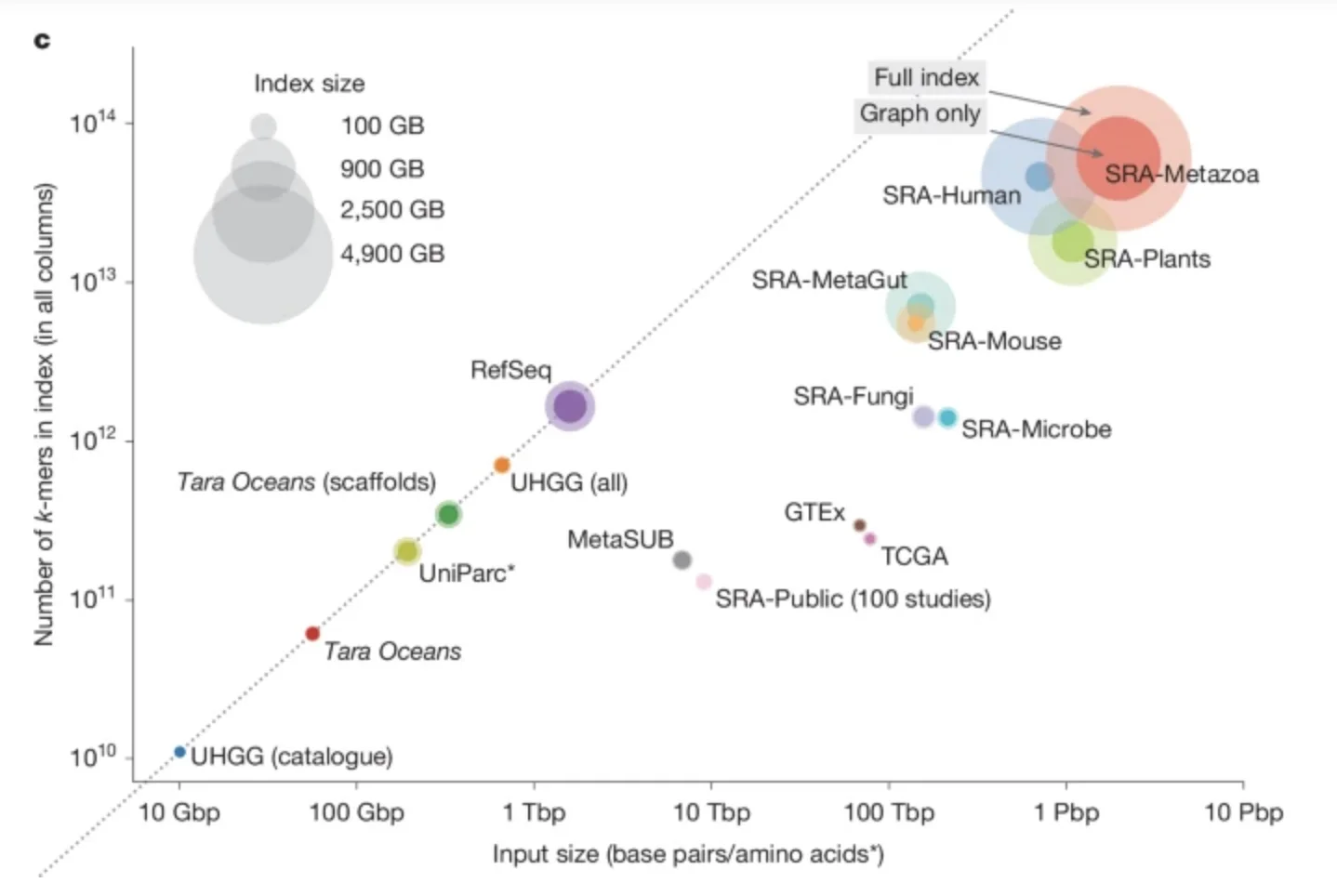

The researchers benchmarked MetaGraph against leading indexing systems including Mantis, Fulgor, Themisto and Bifrost. MetaGraph’s indexes were between 3 and 150 times smaller than competing methods while maintaining similar or faster query times. Even complex searches involving sensitive sequence-to-graph alignment — used to find approximate rather than exact matches — ran efficiently. The system scaled from desktop computers to distributed clusters, demonstrating that petabase-scale search is feasible on academic infrastructure.

In building the MetaGraph repository, the team indexed a vast array of datasets: from The Cancer Genome Atlas and the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project to global microbial collections, ocean microbiomes, and human gut metagenomes. In total, roughly 4.8 petabases of raw data — equivalent to 2.5 petabytes of compressed files — were transformed into compact, searchable indexes. The researchers estimate that extending this to all public repositories would be straightforward.

Biological Insights at Scale

With the system operational, the researchers demonstrated how real-time searches could yield biological discoveries. By querying MetaGraph with the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database and the RefSeq bacteriophage catalog, they identified strong associations between specific bacterial viruses and antibiotic resistance genes. These included correlations between Escherichia λ phages and β-lactamase genes, and between Klebsiella phages and carbapenem-resistance markers. These types of analysis once required hundreds of terabytes of raw data, but could now be completed in about an hour on a single computer. Such capabilities could accelerate medical advances by revealing how resistance genes spread, how viruses interact with bacteria, and where new therapeutic strategies might intervene.

MetaGraph also enabled large-scale searches for circular RNA formations known as back-splice junctions in human tissue data from GTEx and TCGA. The study found over 3,000 previously unmapped circular RNAs, with patterns differing between normal and cancerous tissues. These findings illustrate how indexing entire repositories opens new avenues for discovering rare or context-specific genetic features.

Cost, Limitations and Future Directions

The researchers estimate that indexing all 33 million public sequencing datasets would cost less than a fraction of what it takes to generate or store them. Query costs — already less than $1 per megabase for exact matches — are expected to fall further with cloud efficiencies. Even so, MetaGraph’s creators acknowledge several limitations. The framework is static: updating it with new samples requires partial reconstruction. Its sensitivity also drops when dealing with noisy data, such as long-read nanopore sequences, or when searching for distant genetic homology. Moreover, the system’s reliance on static k-mer alphabets limits its ability to index modified nucleotide types recorded by newer sequencing technologies.

Still, the potential impact looks like it could be huge. The researchers report that MetaGraph could become the basis for a “Google for DNA,” where researchers query the entirety of global genetic data to find variants, track pathogens, or train machine-learning models. Because MetaGraph’s compression ratios reach up to 7,400-fold for redundant datasets and 300-fold on average, these indexes could also serve as training databases for large biological language models, accelerating AI-driven discovery across genomics and drug design.

Beyond its technical achievements, the Nature study signals a shift in how biological data can be managed. Instead of isolated archives accessible only by download, repositories like the European Nucleotide Archive or NCBI’s SRA could integrate search indexes directly into their infrastructure. That would allow researchers to search across species, tissues, and studies in real time, much like searching the web.

The ETH Zurich team has released its indexes from public-access data as open resources on AWS and operates a live web portal called MetaGraph Online, which offers real-time queries against major datasets. For now, throughput is limited, but the proof of concept is clear: petabase-scale data no longer has to be opaque or static.

As the study concludes, building a global search infrastructure for genetic sequences is not only technically feasible but economically rational. The cost of indexing and querying is tiny compared with the billions spent generating the data. MetaGraph’s developers further say that this could serve as the foundation for a new era in computational biology, one where genomic data becomes as searchable, and as accessible, as the Internet itself.