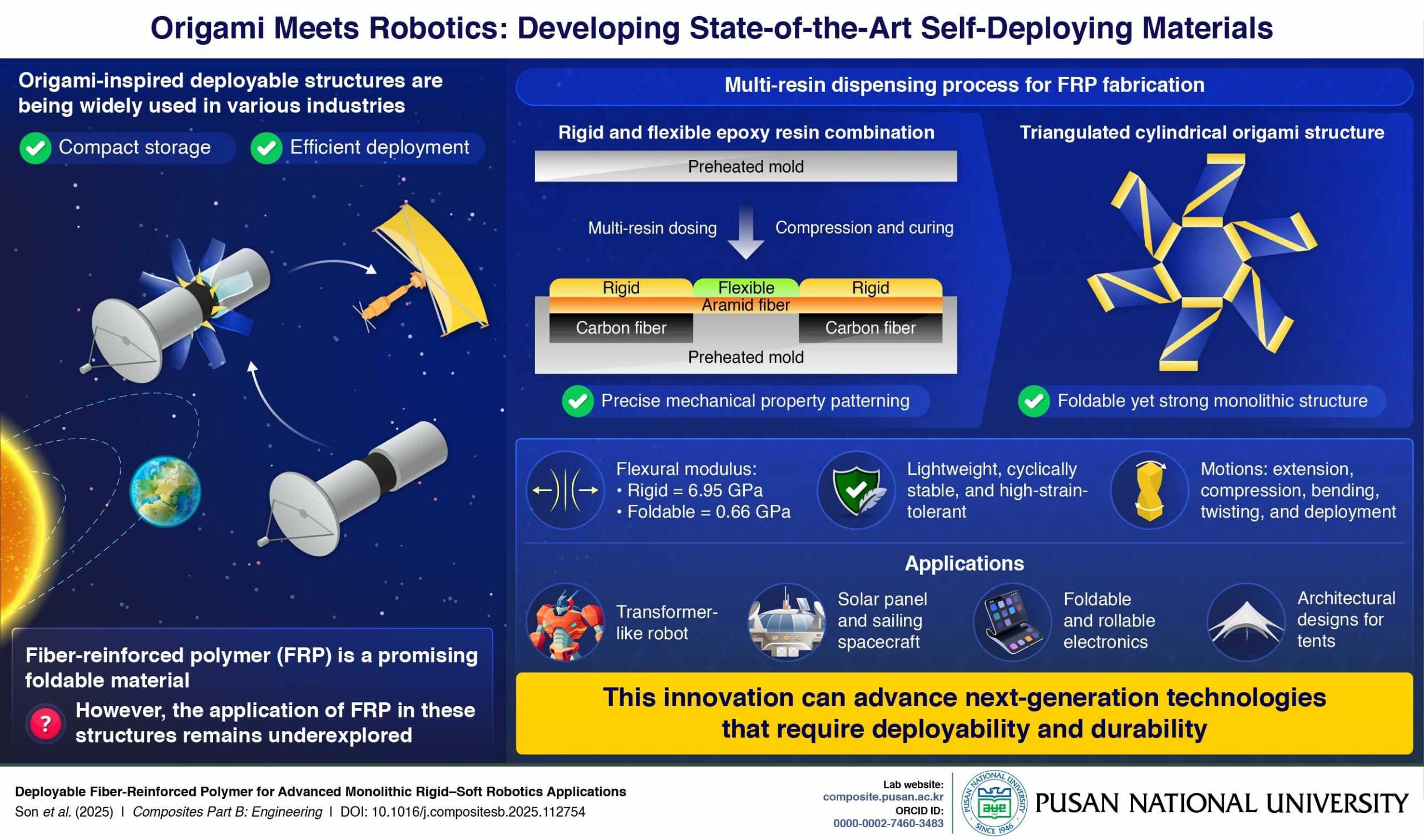

- Researchers at Pusan National University have created a fabrication process for fiber-reinforced polymers (FRPs) that integrates rigid and flexible epoxy resins, enabling selective stiffness in a single foldable structure.

- The method overcomes limitations of traditional single-resin and paper-based materials, allowing origami-inspired designs that are both durable and precisely deployable.

- Published in Composites Part B: Engineering (October 2025), the innovation opens new possibilities for robotics, aerospace, and architecture, including humanoid joints, deployable satellites, and adaptive emergency shelters.

Researchers at Pusan National University have developed a new way to build foldable structures using fiber-reinforced polymers (FRPs), offering a path toward stronger, lighter, and more adaptable designs for robotics, aerospace, and architecture. The study, published in Composites Part B: Engineering in October 2025, introduces a fabrication process that uses two different epoxy resins—one rigid and one flexible—allowing scientists to embed varying levels of stiffness into a single structure.

According to the university, the work addresses a key limitation in soft robotics and deployable designs, where most efforts have relied on materials such as paper, thin glass, or single-resin polymers that lack both durability and precision. By combining rigid and flexible regions within one continuous FRP, the team was able to achieve both structural strength and controlled bending, a balance that has been difficult to realize. Their demonstration included the fabrication of a triangulated cylindrical origami structure, which maintained its strength while folding and unfolding repeatedly.

“Our novel and efficient technique for fabricating composite materials that enable flexible bending while maintaining strong structural performance—an advancement that has not been previously reported in the literature—overcomes the limitations of traditional single-resin systems and manual processes, enabling selective control of rigidity and flexibility within the monolithic composite,” noted Dong Gi Seong, an associate professor in the Department of Polymer Science and Engineering.

Tests showed that the new composites could reach a flexural modulus of 6.95 gigapascals in rigid sections while dropping to just 0.66 gigapascals in foldable ones, researchers said. These variations allowed the structure to bend at radii under half a millimeter without losing stability, withstanding repeated cycles of strain. The structures remained lightweight, durable, and capable of complex movements such as extension, compression, twisting, and deployment.

The implications of this approach are broad, researchers pointed out. The technology could enhance disaster-response shelters, wearable protection, and satellite transport while paving the way for robotics applications such as power suits, humanoid joints, adaptive electronics, and transformable wheels.