Insider Brief

- Researchers at MIT demonstrated that sparse autoencoders can extract biologically interpretable features from protein language models, improving transparency in AI-driven biology.

- The method uncovered features tied to known protein families and processes, including NAD metabolism, methyltransferase activity, and viral translational functions.

- The team reports that these interpretable features could enhance trust, guide drug discovery, and provide safeguards against risks in open-source protein models.

Artificial intelligence models that predict how proteins behave are becoming powerful tools for biology and medicine. But their accuracy comes with a cost: they are black boxes. A new study led by researchers at MIT– paired with IBM’s release of open-source biomedical models — reports that sparse autoencoders can help open that box, extracting biologically interpretable features from protein language models and providing a clearer picture of how these systems arrive at their predictions.

According to the team, the work not only improves trust in protein models but also points toward safer and more effective use of AI in areas such as drug discovery, functional genomics, and biotechnology.

“These models work fairly well for a lot of tasks,” Onkar Singh Gujral, a PhD student at MIT and lead author of the study, told IBM Think. “But we don’t really understand what’s happening inside the black box. Interpreting and explaining this functionality would first build trust, especially in situations such as picking drug targets.”

Protein language models, or PLMs, have rapidly advanced over the past five years. Like their cousins in natural language processing, they are trained on vast datasets — in this case, millions of protein sequences — and can infer the structure and function of proteins with impressive accuracy. ESM2, one of the most widely used PLMs, has been applied to predicting folding patterns, binding sites, and functional annotations.

The problem is interpretability. PLMs make correct predictions but provide little insight into what information they are using or why. That gap undermines trust, complicates regulatory oversight, and slows adoption in critical domains such as drug discovery.

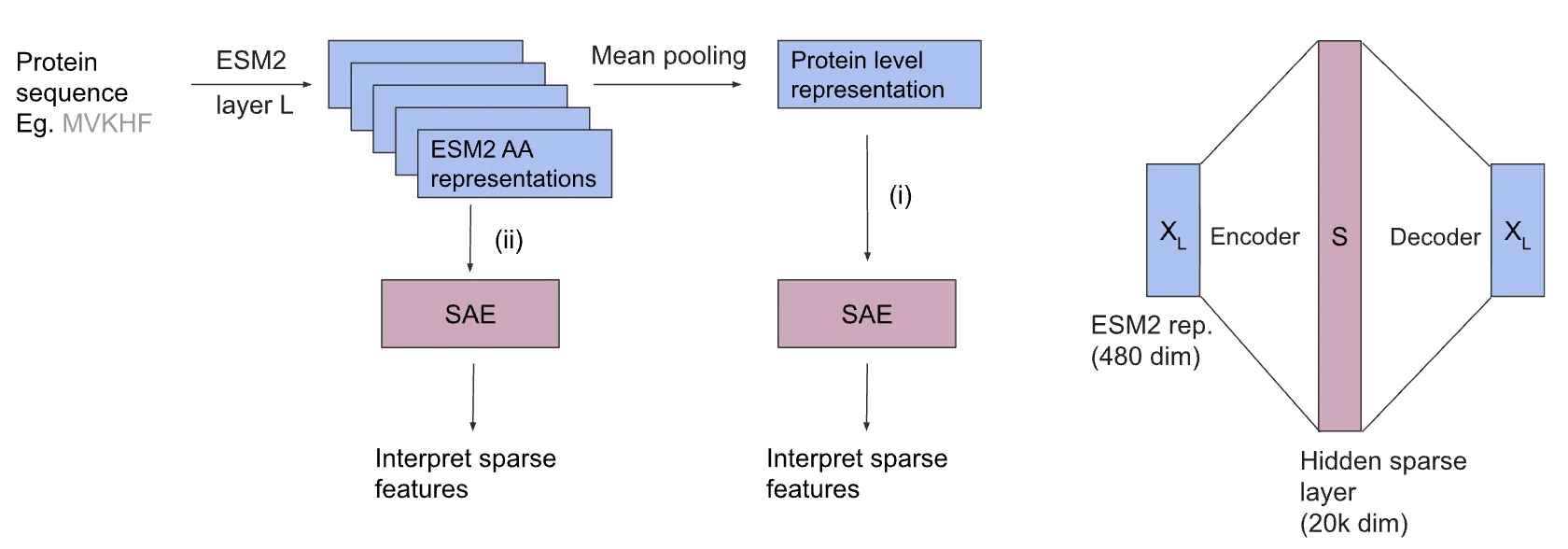

The MIT team set out to address this by adapting sparse autoencoders, a tool recently developed for large language models, to the biology setting. Sparse autoencoders work by disentangling overlapping signals in a model’s neurons, turning polysemantic representations into more interpretable features.

The researchers trained sparse autoencoders and a related method, transcoders, on ESM2’s protein-level and amino acid–level representations. They then analyzed the features that emerged. Many corresponded to known protein families, gene ontology categories, and biological processes, such as NAD metabolism, methyltransferase activity, and viral translational frameshifting.

The team reports that sparse features were consistently more interpretable than the original neurons in ESM2, with interpretability scores substantially higher across all tested layers.

Automating Interpretation

Interpreting thousands of features manually would be impossible. To scale the process, the researchers turned to another AI system: Anthropic’s Claude. They designed a pipeline that fed the model metadata about protein families, gene names, and functional annotations, then asked it to generate human-readable summaries of what each sparse feature appeared to capture.

In this setup, Claude effectively simulated interpretability, predicting which proteins would activate a given feature based on its description. The researchers scored the accuracy of these interpretations and found strong correlations with actual activation patterns, reinforcing the claim that the features corresponded to biologically meaningful categories.

Examples included neurons tuned to the NAD kinase family, proteins involved in iron–sulfur cluster assembly, and enzymes tied to RNA and DNA methylation. In one case, a sparse feature was linked to olfactory and gustatory receptors, suggesting that the method can uncover signals across a wide biological range, from metabolic processes to sensory perception.

Why It Matters for Drug Discovery

The immediate impact of this research lies in interpretability. For drug discovery teams, the ability to understand why an AI model highlights a protein as a promising target is just as important as the prediction itself.

- Trust and regulation: Drug regulators are wary of black-box predictions. Explainable models provide a traceable rationale for decisions, which can support approval processes.

- Target validation: Sparse features allow researchers to pinpoint the biological families or processes driving a model’s outputs, guiding better experimental follow-up.

- Safety and dual-use: Interpretable models make it easier to audit what information is encoded, reducing the risk of misuse if sensitive biological functions are inadvertently captured.

The researchers write that as protein models become more powerful and widely shared, tools that make them transparent will be essential for safe and responsible use.

The Black Box Problem Explained

For readers outside the AI field, the “black box” problem describes a situation where a model produces accurate predictions but hides its reasoning. In protein science, this means a model might correctly predict that a sequence folds into a certain structure or participates in a pathway, but no one knows which features of the sequence drove that conclusion.

Sparse autoencoders help by creating a wider hidden layer that activates sparsely — only a small subset of neurons fire for a given input. This disentanglement allows individual features to map onto clearer biological categories, rather than overlapping in opaque ways.

The result is that instead of an inscrutable vector of numbers, researchers see features tied to known protein families, enzymatic functions, or cellular processes.

Not a Replacement For Predictive Models

Sparse autoencoders are not designed to replace predictive models. They do not directly assign functions to proteins in the way that supervised algorithms do. Instead, they expose which features a model has already learned, providing interpretability rather than classification. In practice, that means these tools are best seen as complements: prediction models identify potential functions, while interpretability methods clarify the biological signals underlying those predictions.

For drug discovery, this added layer of transparency could help reduce wasted effort. By showing why a model flags a protein as significant, sparse autoencoders make it easier for researchers to prioritize targets with clearer biological justification and avoid false leads. The approach is not a shortcut to instant therapies, but it sharpens the connection between computational insights and experimental validation.

The work also highlights risks. As protein models grow more powerful, they may encode sensitive biological information that could be misused. Interpretability tools offer a way to audit what these systems contain, but safeguards and governance will remain necessary. In short, sparse autoencoders increase trust and safety, but they do not make artificial intelligence infallible.

Practical Tips for Industry Teams

For pharmaceutical and biotech professionals exploring AI-driven discovery, the study offers some practical lessons:

- Audit your AI models. Incorporate interpretability checks using tools like SAEs to ensure you understand what drives predictions.

- Pair AI with experiments. Use interpretable features to design targeted laboratory tests, rather than treating predictions as definitive.

- Stay alert to open-source risks. As models get more powerful, organizations should build interpretability into their risk management frameworks.

Limitations

The study acknowledges several limitations and areas for further exploration. The method was tested on mean-pooled protein-level representations, a common choice but not the only way to represent proteins. Other approaches, such as beginning-of-sequence token representations, may yield different interpretability profiles.

The results also depend on the type of autoencoder used. The team employed TopK sparse autoencoders, but other variants such as L1 or gated SAEs could behave differently. Random initialization may also influence the features extracted.

Finally, while the automated interpretability pipeline using Claude was scalable, it was limited to a subset of features. A more exhaustive interpretation might uncover additional biological insights.

The researchers ultimately stress that unsupervised interpretability tools like SAEs are not designed to replace predictive models. They are best used as complementary methods to explain and contextualize predictions.

Future Directions

The researchers point to several avenues for extending their work. One is to test whether different strategies for pooling protein-level representations yield new sets of interpretable features, since the current study relied on a common mean-pooling approach. Another priority is refining amino acid–level analysis to capture features at the resolution of individual residues, such as the catalytic sites that often determine a protein’s function.

The team reports that sparse autoencoders themselves come in different forms, and comparing architectures will be important for ensuring results are consistent and robust. Finally, the methods could be applied to other biological foundation models beyond ESM2, including those focused on genomic data or multimodal systems that integrate several types of biological information.

The researchers also emphasize that interpretability could become a standard tool in the life sciences, much as model explainability is becoming a requirement in finance and healthcare AI.

The study was led by Onkar Gujral, Mihir Bafna, Bonnie Berger and Eric Alm, all at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)..