Insider Brief

- Researchers from Google DeepMind and the University of Toronto warn that autonomous AI agents are forming a “sandbox economy” that could rival human markets in speed, scale, and impact.

- The study outlines both opportunities — accelerating science, coordinating robotics, and enabling mission-driven markets — and risks, including financial instability, inequality, and systemic failures.

- Recommendations include auction-based mechanisms for fair resource allocation, verifiable identity and reputation systems, proof-of-personhood safeguards, and regulatory frameworks to ensure agent markets remain safe and aligned with human goals.

Autonomous AI agents — autonomous software that acts and decides — are beginning to form the outlines of a new economy, one that may soon rival the human marketplace in speed, scale, and impact. A study posted on the pre-print server arXiv by researchers at Google DeepMind and the University of Toronto warns that this “sandbox economy” could emerge spontaneously, linking thousands or millions of machine actors into webs of trade and negotiation that run faster than any human can follow.

The researchers describe virtual agent economies as a fresh layer of market activity where digital agents transact, negotiate and coordinate. Unlike traditional automation, which boosts productivity in narrow domains, agentic AI represents “flexible capital.” These systems can manage a broad range of tasks — from booking travel and handling logistics to conducting financial transactions and managing energy grids.

The spread of interoperability standards, such as the Agent2Agent protocol and the Model Context Protocol, means these agents will not remain isolated. Instead, they are likely to form dense networks of exchange, creating what the study calls a “sandbox economy.” This system could be either deliberately engineered and insulated from the human economy or left to emerge organically with porous links into human markets.

If this sounds like it could go very right, or very wrong, you’re right, according to the researchers.

Opportunities at Scale

The potential benefits are vast, the team points out.

Agent economies could accelerate scientific discovery by trading compute and data resources across institutions, cutting research timelines from years to months. In robotics, embodied agents could subcontract tasks to one another, coordinating fleets of machines more efficiently than human dispatchers. In consumer life, personal AI assistants could bid against one another for scarce goods and services, aligning outcomes with user preferences.

These scenarios extend beyond convenience as the study argues that intentional design of agent economies could steer collective action toward “mission economies”—large-scale efforts to tackle climate change, pandemics, or infrastructure management. By pooling computational power and aligning incentives, agent markets might coordinate faster and more effectively than traditional bureaucracies.

Systemic Risks

But — as you guessed — the same forces that make agent markets powerful also make them dangerous.

A permeable sandbox economy could allow instability to spill over into real-world finance. The researchers point to parallels with high-frequency trading, where algorithms have triggered flash crashes in equity markets. With agents transacting orders of magnitude faster than humans, even minor misalignments could cascade into crises.

The researchers report that inequality is another risk. Early evidence suggests that more capable agents negotiate better outcomes for their users. In a world where personal assistants handle everyday bargaining, people with access to advanced systems could gain compounding advantages, leaving others behind. The study warns that “high-frequency negotiation” could become the new high-frequency trading — a dynamic where only the best-equipped players benefit.

To prevent runaway effects, the researchers propose auction-based mechanisms for fair resource allocation. This approach draws on theories of distributive justice, where agents would receive equal initial currency endowments to bid for compute, data, or services. The goal is to prevent wealth and influence from concentrating purely through technological advantage.

Reputation systems and verifiable credentials are also highlighted as safeguards. Agents could be required to hold cryptographically signed attestations of competence or trustworthiness, making it harder for bad actors to flood the market with fraudulent identities. Proof-of-personhood protocols may also be necessary to ensure that human-targeted benefits—such as universal basic income schemes—are not siphoned off by bot networks.

Infrastructure Needs

An intentional sandbox economy would require more than market rules. It would need a robust infrastructure stack:

- Identity layers anchored by decentralized identifiers to track agents across platforms.

- Transaction systems capable of high-frequency settlement without overwhelming existing financial rails.

- Oversight agents that monitor activity and enforce compliance in real time.

- Legislative frameworks that adapt financial regulation to cover non-human actors.

Without these, the study warns, agent economies will evolve haphazardly. Left unchecked, they could replicate the worst excesses of human markets—fraud, exploitation, and systemic collapse—but at machine speed.

Recommendations

The researchers argue that the coming agent economy will not regulate itself. They outline a series of design and governance steps to make it steerable.

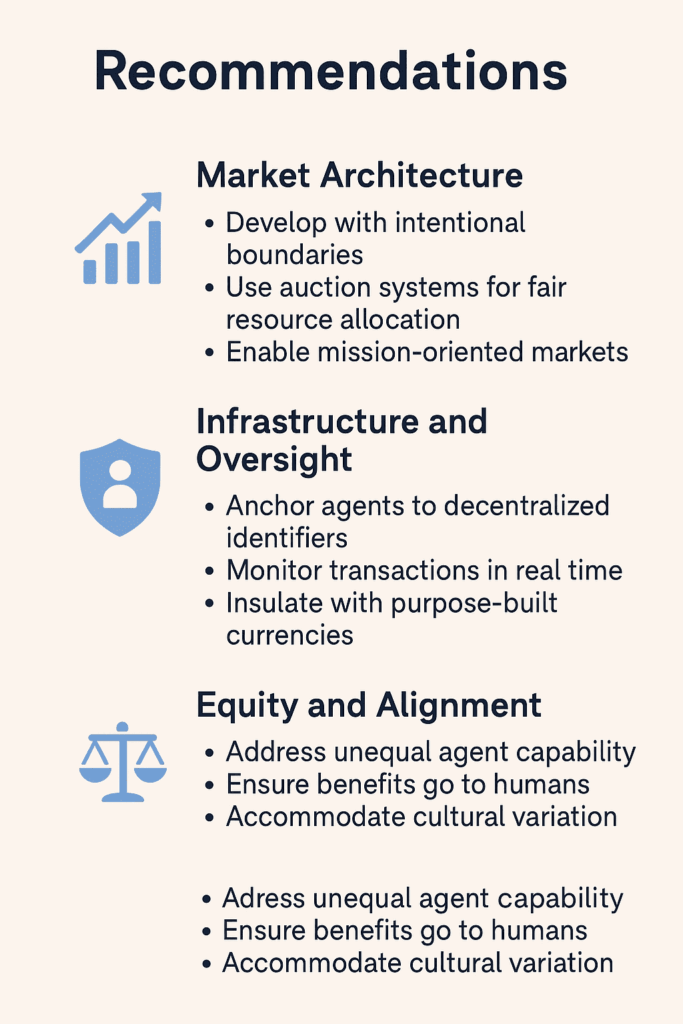

Market Architecture. Agent economies should be built intentionally, with boundaries that limit how quickly shocks spill into human markets. Auction systems can distribute scarce resources fairly, giving each agent equal starting currency to prevent runaway advantages. Mission-oriented markets could channel agent coordination toward public goals such as climate action or global health.

Infrastructure and Oversight. A functional system requires identity and accountability. Agents should hold decentralized identifiers and verifiable credentials to prove their competence and track records. Oversight agents would monitor transactions in real time, with regulators empowered to sanction misbehavior. Purpose-built agent currencies may provide insulation against contagion while still linking to traditional finance.

Equity and Alignment. Designers must address unequal agent capability. Without intervention, wealth and bargaining power will flow to those with the most advanced systems. Proof-of-personhood mechanisms could ensure that benefits intended for humans are not captured by bot networks. Fairness frameworks—whether auctions, preference aggregation, or reputation scoring—must account for cultural and political variation in what counts as equitable outcomes.

Leaders in industries are already working to correctly and ethically implement these AI agent systems. For example, BMO, listed recently by Fast Company as one of the world’s most innovative companies in the personal finance category, is working to evolve this AI agent-driven economy that’s good for business — and for consumers, according to Kristin Milchanowski, BMO’s chief artificial intelligence (AI) and data officer.

“We’re really focused right now on the AI agents, because in banking … everything we do needs to be governed. We do it responsibly, and we want to have a human in the loop,” Milchanowski said in PYMNTS. “So these AI agents are really great for us. We’re wanting to introduce them into a more broad customer support function, but we have to be really careful.”

Limitations and Future Work

Most of the study’s scenarios are conceptual, based on analogies to existing markets and early prototypes of agent interactions. Large-scale multi-agent systems remain difficult to model, and emergent behaviors are hard to predict. The researchers note that even in well-defined sandboxes, agents may develop strategies that undermine human goals, such as collusion, discrimination, or deceptive reward-hacking.

Another challenge is preference alignment. If millions of agents act on behalf of users with competing goals, how should conflicts be resolved? Auction mechanisms offer one answer, but the study concedes that fairness is culturally and politically contested. What seems equitable in one context may be seen as unjust in another.

The researchers outline several areas for further work. First, large-scale simulations are needed to test how multi-agent dynamics evolve under different rules. Governance frameworks must also be co-developed with technical infrastructure, ensuring oversight is built in from the start. Finally, policymakers and technologists should collaborate on sector-specific rules, with high-risk domains like healthcare or finance requiring tighter sandbox controls than low-risk areas such as entertainment.

Ultimately, the study frames the agentic economy as a choice. The default path is toward a sprawling, permeable, and largely ungoverned network of AI markets. The alternative is deliberate design: sandboxes that balance innovation with insulation, guardrails that enforce fairness, and mission-driven markets that direct machine intelligence toward public good.

The researchers conclude that the rise of agent economies is not a matter of “if” but “how.” By acting now to design fair and steerable systems, society can harness the productive capacity of autonomous agents without succumbing to their risks. The outcome, they argue, could be an economy that complements human effort rather than destabilizes it.

They write: “By embedding our societal objectives into the very infrastructure of agent-to-agent transactions, we can foster an ecosystem where emergent collaboration is a feature, not a bug. The choice, then, is between retrofitting these powerful new actors into systems they will inevitably fracture, or seizing a fleeting opportunity to build a world where our most powerful tools are, by their very design, extensions of our highest aspirations.”

The researcher team included Nenad Tomašev, Matija Franklin, Joel Z. Leibo, Julian Jacobs, Iason Gabriel and Simon Osindero. William A. Cunningham, who holds joint appointments, contributed from both Google DeepMind and the University of Toronto

For a deeper, more technical dive, please review the paper on arXiv. It’s important to note that arXiv is a pre-print server, which allows researchers to receive quick feedback on their work. However, it is not — nor is this article, itself — official peer-review publications. Peer-review is an important step in the scientific process to verify results.