Insider Brief

- Duke University researchers have developed an AI framework that converts complex, nonlinear dynamical systems into compact, interpretable linear models that preserve accurate long-term behavior.

- The system analyzes time-series data using deep learning and physics-inspired constraints to identify a small set of hidden variables, often reducing model size by more than an order of magnitude compared with prior machine-learning approaches.

- Demonstrated across physical, electrical, climate, and neural systems, the approach enables interpretable prediction, identification of stable states, and scientific insight when governing equations are unknown or impractical to derive.

PRESS RELEASE — A research team at Duke University has developed a new AI framework that can uncover simple, understandable rules that govern some of the most complex dynamics found in nature and technology.

The AI system works much like how history’s great “dynamicists” – those who study systems that change over time – discovered many laws of physics that govern such systems’ behaviors. Similar to how Newton, the first dynamicist, derived the equations that connect force and movement, the AI takes data about how complex systems evolve over time and generates equations that accurately describe them.

The AI, however, can go even further than human minds, untangling complicated nonlinear systems with hundreds, if not thousands, of variables into simpler rules with fewer dimensions.

The work, published December 17 online in the journal npj Complexity, offers scientists a new way to leverage AI to help understand complex systems that change over time—such as the weather, electrical circuits, mechanical systems and even biological signals.

“Scientific discovery has always depended on finding simplified representations of complicated processes,” said Boyuan Chen, director of the General Robotics Lab and the Dickinson Family Assistant Professor of Mechanical Engineering and Materials Science at Duke. “We increasingly have the raw data needed to understand complex systems, but not the tools to turn that information into the kinds of simplified rules scientists rely on. Bridging that gap is essential.”

The trajectory of a cannon ball depends on many variables such as exit velocity and angle, air drag, varying wind speeds, and even ambient temperatures, among many others. However, a very close approximation can be found by a simple linear equation that only uses the first two.

This is an example of a theoretical idea originally proposed by mathematician Bernard Koopman in the 1930s: Complex nonlinear systems can be represented mathematically by linear models. The new AI approach builds on this concept.

There is, however, a catch. To find linear models of extremely complex systems, one needs to develop hundreds, if not thousands, of equations involving just as many variables. And human minds do not handle such large numbers very well.

That’s where AI comes in handy.

The new framework examines time-series data from experiments, identifies informative patterns in how the system evolves, and uses deep learning together with physics-inspired constraints to distill a far smaller set of variables that still captures the system’s essential behavior. The result is a compact description of a system that behaves mathematically like a linear one yet still reflects the complexity of reality.

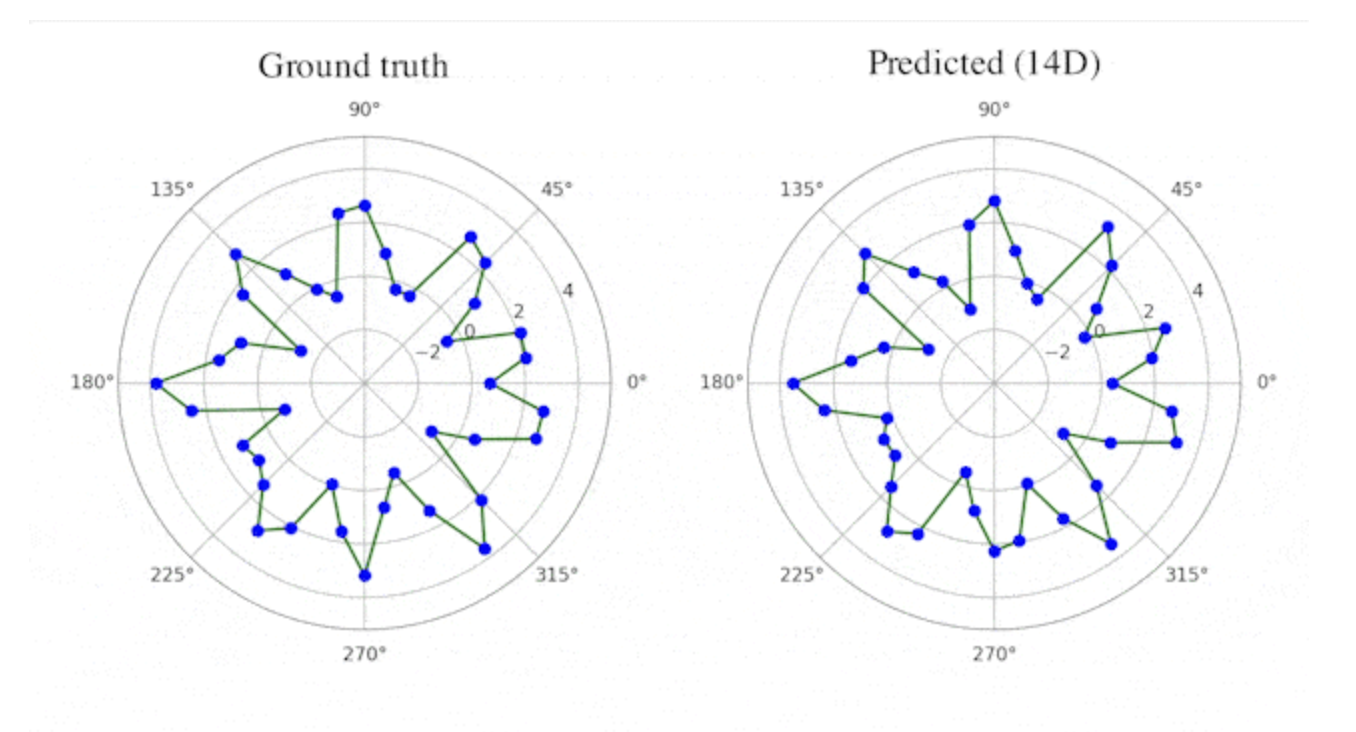

The team applied their framework to a broad range of systems, from familiar motions of a pendulum to nonlinear rhythms of electrical circuits, to models used for climate science and neural circuits. Despite their differences, each system revealed a small set of hidden variables that governed its behavior. In many cases, these reduced models were more than 10 times smaller than what previous machine-learning approaches required while still providing reliable long-term predictions.

“What stands out is not just the accuracy, but the interpretability,” said Chen, who also holds appointments in electrical and computer engineering and computer science. “When a linear model is compact, the scientific discovery process can be naturally connected to existing theories and methods that human scientists have developed over millennia. It’s like connecting AI scientists with human scientists.”

Beyond prediction, the framework can identify stable states, known as attractors, where a system tends to settle over time. These states are crucial for understanding whether a system is behaving normally, drifting or heading toward instability.

“For a dynamicist, finding these structures is like finding the landmarks of a new landscape,” said Sam Moore, the lead author and PhD candidate in Chen’s General Robotics Lab. “Once you know where the stable points are, the rest of the system starts to make sense.”

The researchers emphasize that the method is particularly useful when traditional equations are missing, incomplete, or too complicated to derive. “This is not about replacing physics,” Moore continued. “It’s about extending our ability to reason using data when the physics is unknown, hidden, or too cumbersome to write down.”

Looking ahead, the team is exploring how the framework could guide experimental design—actively choosing what data to collect to reveal a system’s structure more efficiently. They also envision applying the approach to richer forms of data, such as video, audio or signals collected from complex biological systems.

This research is part of a long-term mission in Chen’s General Robotics Lab, where the team aims to develop “machine scientists” to assist automatic scientific discovery. By bridging modern AI with the mathematical language of dynamical systems, the work points toward a future in which AI does not just recognize patterns, but helps uncover the fundamental rules that govern the physical and living world.

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship, the Army Research Laboratory STRONG program (W911NF2320182, W911NF2220113), the Army Research Office (W911NF2410405), the DARPA FoundSci program (HR00112490372), and the DARPA TIAMAT program (HR00112490419).

CITATION: Automated Global Analysis of Experimental Dynamics through Low-Dimensional Linear Embeddings. Samuel A. Moore, Brian P. Mann, Boyuan Chen. npj Complexity, 2025. DOI: 10.1038/s44260-025-00062-y

Project Website: http://generalroboticslab.com/AutomatedGlobalAnalysis

Video: https://youtu.be/8Q5NQegHz50

General Robotics Lab Website: http://generalroboticslab.com